If you think launching was hard work, try closing your nonprofit. The hardest part of all might be asking the BIG question.

A number of years ago while searching for housing in advance of a move to a Midwest college town, I called Gerry, who was listed as the Board President for a nonprofit cooperative house near campus. “Oh no,” he replied, “We closed back in the 80’s. Sold off the property. Put the money into some type of trust.”

Several months later, after my move, a casual conversation with a local banker revealed the assets from that sale were still parked in an account: $120,000.

Back to Gerry. “The end was chaotic. I roomed there during my college years in the wild 60s. Great place. Fond memories, but the house took a lot of wear and tear. I joined the Board in ’82, and it was just one costly problem after another; the roof, the electric, the furnace. Ate into all of our reserves. Final straw was taking a loan to replace the water main. Within a year the writing was on the wall.”

Rather than wait for the sheriff to appear they sold off. The Board then deposited the proceeds into a bank account and walked away. There the money sat until I came along 12 years later.

Launching your nonprofit is complex. Closing your nonprofit is doubly so. The same government agencies that were involved in starting nonprofit are equally engaged when you shutter. Failure to do it right is dangerous because until the nonprofit is legally dissolved, the board members and officers still have continuing fiduciary and legal responsibility.

In this case, Gerry and I worked together to contact an attorney and the state, reconstituted the Board for a final vote to close and disburse the assets to several human service providers. Next was filing the final dissolution documents which officially put this nonprofit out of business.

This case was a mixed bag of right and wrong. What the Board did right was to clearly examine the business – the income, the expenses, the trends – and determine that the best step was to close before, figuratively, the house was on fire. Their failure was in not following the administrative steps all the way to the end to ensure legality.

But let’s make it clear, they got the important thing correct. They looked at the numbers, considered the options, thought strategically and consciously answered the question, “Can we exist as an independent organization?”

The Big Question

In a time of incredible transformation where there is a fundamental reset of our basic economy, the “Big Question” that nonprofit leaders must answer is, “Can we exist as an independent organization?” Far too often, nonprofits avoid the question until insolvency. Sometimes it’s a lack of awareness and sometimes it is outright denial. Two examples in the first half of 2012 show the benefits of doing it right and the consequences of doing it wrong.

The Stunning Collapse of Hull House

It was big. It was rich in history and it was large in scope; thus the dramatic news in January 2012 that after 123 years serving the needs of low income/immigrant people in Chicago, Hull House was bankrupt. On that winter day, it shuttered its doors and dismissed more than 300 employees.

The news was particularly jolting because of its iconic status. Hull House, started in 1889 by the sociologist Jane Addams, began as a settlement house that worked to “Americanize” Chicago’s immigrants and help the city’s poorest citizens improve their lives. Ms. Addams’ work on issues involving women, children, and public health proved widely influential; she won a Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts in 1931

It didn’t take long picking through the rubble to see that Hull House had been sliding toward disaster for 10-15 years. While expenses were growing and revenues shrinking, the staff continued to paint an optimistic picture of things while the Board failed in its basic fiduciary responsibility to ensure that the organization was solvent. That’s not to say that the staff deceived the Board. Over the past decade, the Board received the numbers and the red flags were waving all over the place: increasing dependence upon government money, decreasing local cash contributions, growing debt, cash flow crunches, impotent fundraising power of the Board.

Even in the end, the Hull House Board showed remarkable denial about the level of decay. Stephen Saunders, who took control of Hull House’s board 18 months ago said, “If someone had given us a $2-million check, that would have given us time to right the ship.” He later added that he would have hired a good fund-raising consultant, sought more help from private donors and set a goal of reducing the share of government support from 85 percent to 75 percent; but even that was unlikely to help given the soft state of the economy in addition to the fiscal nightmare facing the Illinois state government.

Public/Private Ventures Exits With Grace and Style

The use of research and evaluation in programming is one of the nonprofit megatrends of the past generation. A leader in this field is the Philadelphia based Public/Private Ventures (P/PV), a 35-year-old nonprofit performing research and evaluation to strengthen social programs for populations such as recently released prisoners and poverty-stricken youth. Whenever you’re reviewing the research behind Big Brothers/Big Sisters and the Nurse-Family Partnership, you’re reading the work of Public/Private Ventures.

Thus people in the know were equally surprised by the March 2012 announcement that P/PV would be winding down operations and closing a nonprofit.

The story emerged that the Board was working for more than a year to find a new business model, one which would be sustainable in light of decreased funding. P/PV had core support from several private foundations as well as from generous individuals, so it wasn’t like the organization was irrelevant. However, in that strategic visioning process, the Board concluded that the changing trends made them non-competitive as a small, mission-focused agency. Thus, they made the difficult decision to gradually disband.

“We had been monitoring our finances pretty closely,” said Nadya Shmavonian, P/PV President. “As a relatively small organization trying to compete on a project basis in a very competitive environment, it’s very difficult to support the margins that are necessary to run an organization.”

By not waiting for a crisis, the Board gave Public/Private Ventures time to dissolve in a manner which supported all stakeholders. Leadership has mapped out what it takes to responsibly cease operation: satisfying funder requirements, seeing staff through the transition and relocating the work. The organization will attempt to finish some of its ongoing projects while moving others to other nonprofits. It is hoped that some of P/PV staff will travel with their projects to the new organization.

And it all started because the Board asked The Big Question.

So Ask It

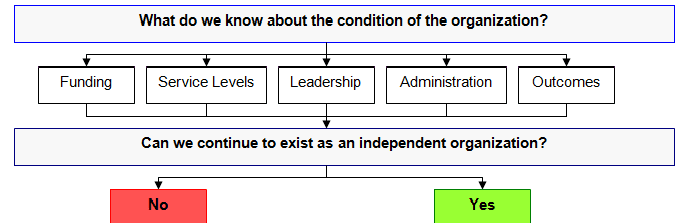

In order to get to The Big Question about closing your nonprofit, it may first be helpful to ask a series of smaller questions. These are grouped under “What do we know about the condition of the organization?”

- Funding – What’s our funding mix? What are the trends? Do we have significant local support?

- Service Levels – What are the trends? The demographics?

- Leadership – Do we have a full Board roster? Are Board members actively engaged? Do they provide talent as well as significant financial contributions?

- Administration – Do we have the right talent in the right slots to carry out our strategic priorities?

- Outcomes – Are we effective? Can we prove that we are a good investment?

Realistically, these smaller questions should be driving the majority of Board discussions – in good times and bad; but for leadership that is trying to get the conversation going regarding closing your nonprofit. The following flow chart can help Board members visualize where this discussion needs to go.

It is in this framework a Board can intelligently discuss The Big Question. Nonprofits that will survive the age of austerity will have some common characteristics: strong boards with leaders who possess strategic awareness, who are grounded in fiscal reality as well as contributing financially themselves.

But as each day brings more evidence that business as usual is a losing strategy, failure to confront The Big Question can lead to catastrophic consequences. Sudden collapses are devastating for the people who rely upon nonprofit services help as well as for staff who rely upon the job to pay their bills. It is the responsibility of the Board to avoid these traumatic scenarios.

# # #

Photo Credits: Markus Spiske via @unsplash, Public/Privatre Ventures and Hull House